Untold Lessons from My Father

/Melchor Diokno and his family, right to left, son Rudy, wife Felicidad, Diokno, and the author, before Christmas midnight mass, 1960 (Photo courtesy of Ed Diokno)

One day when I was seven or eight, he took me to get a haircut at the International Hotel in San Francisco’s Manilatown. I thought it strange because for two bits, we could get a haircut just down the street at Mr. Willis’ house. A former barber, Mr. Willis had set up shop in his garage, and that’s where everybody in the Warren Way neighborhood got their haircuts.

The I-Hotel was home for many of the manongs, the elderly men who made up the first wave of Filipino immigrants who came to the United States in the 1920s-1930s. They found jobs in California’s farm fields and worked in the kitchens of the city’s hotels and restaurants. Some found a career in the Merchant Marines and lived in the residential hotels of Manilatown between journeys.

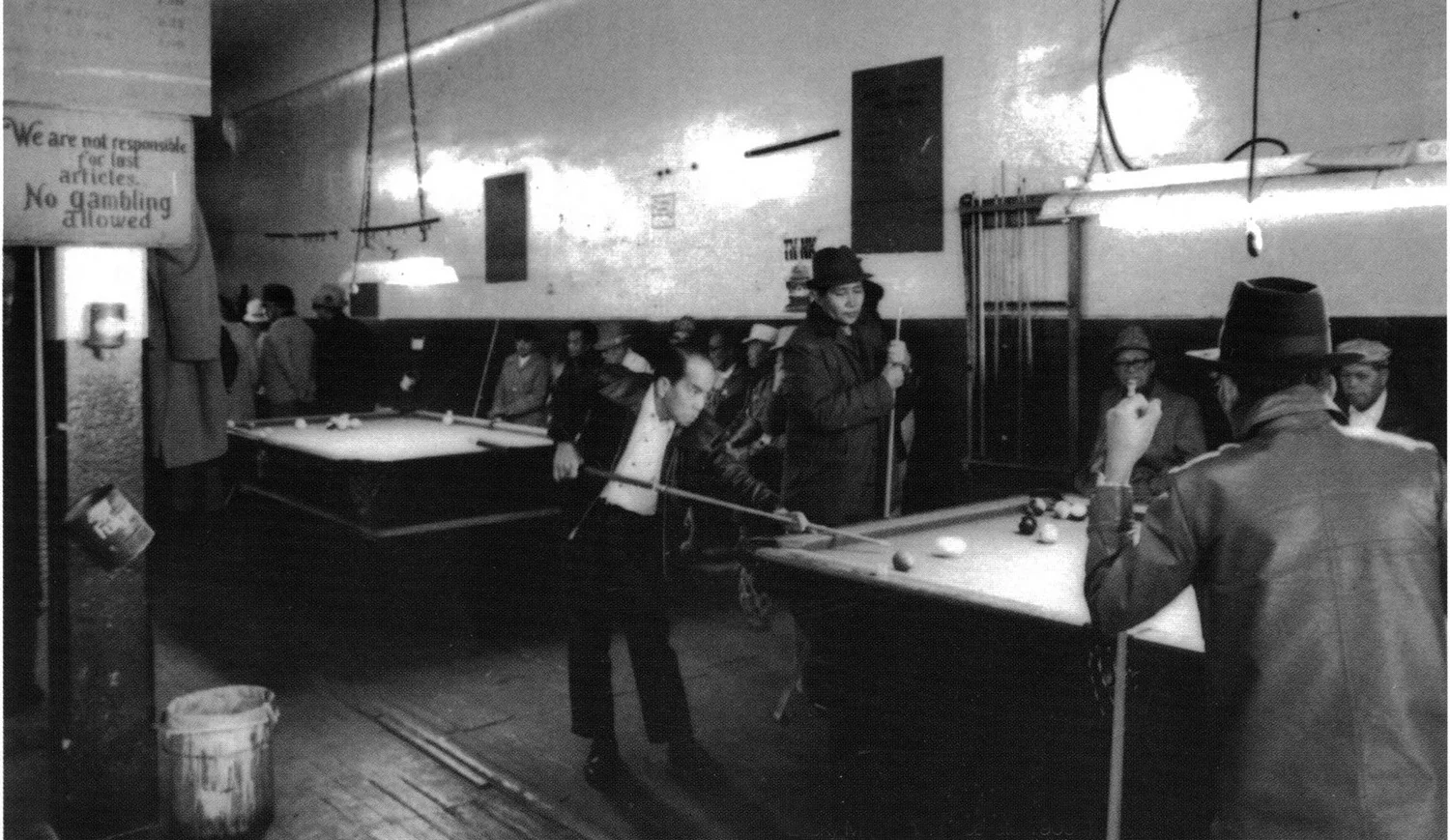

Manongs playing billiards at the I-Hotel (Source: Filipinas Magazine, October 1997)

Manilatown used to stretch for blocks along Kearny Street, just below Chinatown. By the time my father and I made our trip, the financial district had gobbled up most of Manilatown. All that was left of the Filipino neighborhood was the hotel, two Filipino restaurants and the pool hall across the street managed by a white woman who had married a Filipino. Still, for hundreds of Filipino bachelors (because immigration law limited the number of Filipinas) it was a home.

We walked up the hotel’s stairs and knocked on one of the doors. Inside were a couple of elderly men waiting for a haircut from the room’s tenant. In the corner there was a single bed, a bureau where a statuette of the Virgin Mary was framed by a pair of unlighted candles, a cushioned chair covered with a doily and a high stool on which one of the men sat with a bed sheet draped around his neck. Old photos were pinned up around the small room. It had the smell of a barbershop, with the whiff of after-shave and pomade.

“Captain,” they greeted my dad, “How are you, sir? Have a seat, sir.” My father retired as a major but apparently old habits died hard for these men. They spoke in Tagalog with my father. As a young child in the 1950s, my immigrant parents instilled in me the importance of learning English, the language of our adopted land; thus, I lost my ability to speak Tagalog.

Capt. Melchor Diokno (center, front) with the other officers while stationed in Korea, 1953-54. (Photo courtesy of Ed Diokno)

I was never sure how my father knew these men so far from my little world in suburbia. By the respect they showed him, I surmised they used to serve together in the military. After I got my haircut, my father took me next door to a restaurant on Kearny. To my surprise, the owner greeted my father like an old friend. He ordered some Filipino dishes that he knew I liked: dinaguan, adobo, kare-kare and pancit (pork blood stew, chicken in vinegar sauce, beef stew with peanut sauce, and a Filipino variation of chow mein, respectively).

My father grew more mysterious to me. The man I never knew. Why was he so well known there?

I didn’t know then what I know now. My father wanted to expose me to a world beyond Pittsburg, our suburban town east of San Francisco. He wanted to show me how lucky we were, and that not all Filipinos were as well off as we were on our blue-collar street.

And I learned there was more to my father than I knew. He was one of the founding members of the Fil-Am Council, one of the initial attempts to unite the many Filipino organizations under an umbrella agency. This meant many late night meetings in San Francisco, and his parental absence was not unusual.

“It’s funny but we usually think of our fathers as old men. We forget that once they were young and faced life with youthful optimism with the world at their doorsteps.”

One night, my father came back from one of his innumerable meetings. He was excited. “We got the money!” he exclaimed to my mother. It turns out he was trying to get funding to build retirement housing for farm workers. He and his group were able to raise the money to build Agbayani Village in Delano, where retired farm workers without families to take care of them, could spend their retirement.

The historic significance of my father’s late night meetings took years to dawn on me: That he knew Larry Itliong, one of the founding Filipino leaders of the United Farm Workers, was astonishing to me. My father brought groceries to the grape strikers. He lived part of the Asian American history.

Ironically, I found myself covering the eviction of the I-Hotel’s manongs as a reporter for the Philippine News. The lessons my father sought to teach me during that single visit for a haircut came flooding back in an “aha” moment as Manilatown’s last building fell victim to a wrecking ball.

Residents and supporters line-up in front of the I-Hotel to prevent its shutdown in 1977 (Photo by Crystal Huie. Source: Manilatown Heritage Foundation/Filipinas Magazine, October, 2002)

After my father’s death, I found a black-and-white snapshot of a young man, in a white, blousy shirt, dark pants, boots and — this is what stood out — a sash around his waist. The man in the picture was dashing and handsome in a Rudy Valentino kind of way. His smoldering, dark eyes stared defiantly back at the camera. I couldn’t believe it was a photo of my dad.

It’s funny but we usually think of our fathers as old men. We forget that once they were young and faced life with youthful optimism with the world at their doorsteps.

My dad died years ago before we could have that father-son talk that both of us seemed to avoid. Just as I was realizing the value of what he taught me, he was gone. I like to imagine that if we have a conversation now we’d have lots to talk about.

Ed Diokno is a former editor at the Philippine News, Oakland Tribune and the Contra Costa Times. He is currently working on a historical novel and compiling his writings into a book. He recently began writing a blog, “View from the Edge” at dioknoed.blogspot.com. A version of this commentary appeared in the Contra Costa Times, June 27, 2004.