The Taming of an Obsessed Filipiniana Collector

/The author’s parents (1948)

My parents were important influencers. My father was a military man who thought books, not toys, were good for me.

He had subscriptions for me to Popular Science and Mechanics Illustrated, hoping I’d become an astronaut one day. One birthday present he gave me was a dictionary, and he expected me to read it from cover to cover. I did, though I was a very unhappy birthday boy. But today, I can still remember many words, and if there are those that I now have forgotten, well there’s Dictionary.com or Google.

My mother was a book worm. She was always reading, the daily newspapers, magazines, books. There were times of the day we were not to bother her for she was reading and didn’t want the company of children. She got me subscriptions to Reader’s Digest and National Geographic.

National Geographic introduced me to a world to explore. I developed a love for reading more about those parts of the world. My desire to travel started; a wanderlust as Jose Rizal would call it. I was quite proud when the Philippines was featured in National Geographic.

National Geographic

In the houses we lived in, there was always a section called the library. It was often just one wall of books, but it was enough to have a quiet place to read.

In grade three, a classmate brought a book to school, and during recess he’d make sure no one was around and he’d open the book. I was surprised at the drawings. They were erotic Shunga drawings with men and women in various sexual poses. We giggled and were slightly disturbed. These drawings were more interesting than naked men and women in biology books that stood upright, just posing. I realized how a book can affect you. It was my first encounter with artistic pornography.

In La Salle Green Hills High School, our senior classrooms were in this modern Brutalist architecture, designed by Gines Rivera.

English classes which included book reading assignments were my favorite. One book, The Diary of Anne Frank, impressed me. This young girl recounted her family life and first love under very dangerous circumstances. Being Jewish, they had gone into hiding. Later discovered, Anne would die in a concentration camp just days before it was liberated. Her story made such an impact to people all over the world. I thought about her life and it made me oppose all wars from then on.

The Diary of Anne Frank

In high school, I joined the literary club and wrote for the journal and the school paper, which got me to read more. I was tagged as a bookworm. In keeping with appearances, I made sure I carried books around campus and wore large round glasses.

The book that set me off to collecting Filipiniana was Leon Wolff’s Little Brown Brother. Our history classes in high school didn’t cover the Philippine-American War. We were studying the American version which went like this: There was a despotic general named Aguinaldo who was a nuisance to America’s effort to save the country.

Little Brown Brother revealed Filipino soldiers fighting under a general, liberating this country from Spain and then resisting the United States in vain. Finding out that hundreds of thousands of combatants and civilians fought and died for independence made me curious to know more about our hidden history. I started to buy Filipiniana books from Popular Bookstore, Solidaridad Book Shop, and Erehwon.

Little Brown Brother

I was a member of the student organization SDK. We thought of ourselves as the intellectual organization; the KM to us was more muscle than brains. Or so we thought. But being in SDK introduced us to all the readings of Marx, Lenin, and Mao’s Red Book that I purchased years ago in a communist store in Hong Kong. That store is now an Armani X.

My eclectic taste in books probably saved me from falling into the dogmatic mindset of the communists. Aside from Mao, there was James Baldwin, Gore Vidal, Emma Goldman, and a host of other independent free thinkers who were radical in their own ways.

I also had a rule for buying books in those days. Whatever was considered obscene and banned by the moral authorities, especially the Catholic Church, I immediately went out and bought it. In my library, there was Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence, Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller, Jean Genet’s Our Lady of The Flowers, and many other books that got me many mortal sins, even an excommunication threat.

When I was in the United States finishing my studies, there were Filipiniana materials to be found everywhere for my collecting mania.

When Martial Law was declared in 1972, there was a warrant for my arrest. I had helped found and wrote for an anti-dictatorship newspaper, Kalayaan and was photographed demonstrating in front of the Philippine Embassy. I couldn’t go back to the country just yet so I made my stay useful by hunting for Filipiniana. Being in exile, knowing you couldn’t go back, made collecting anything Philippine more personal to me.

I lived in New York, the center for antiquarian books in the United States. I’d enter these stores and ask, “Do you have anything on the Philippines?” More often, I was told they had sold all their Philippine material to a Filipino gentleman whose name was Eugenio Lopez.

Eugenio Lopez, Sr.

Eugenio Lopez was the industrial magnate (he also received an arrest warrant) who owned, among other things, the Manila Chronicle, ABS-CBN and the Lopez Museum and Library, which was then a block from Roxas Boulevard.

That modern wedge of a library designed by Angel Nakpil, was like a ship about to slide into Manila Bay. I visited and researched there several times and remember being enthralled by a photo album owned by Jose Rizal’s family. Seeing and holding it made Rizal human rather than the martyred saint we were raised to believe.

The Lopez Memorial Museum

I once found in a bookstore a large two-volume book, called Our Islands and Their People. I felt quite smug thinking I had beaten Mr. Lopez to this set, only to find out later that what I had purchased was common and easy to get. The book was a bestseller in its time, so there were many hundreds of copies to be found everywhere.

Antiquarian bookstores or antiques stores with a book section, many of them outside of New York City and dotting the northeast states, were likely to have Filipiniana. My partner, Jonathan Best, and I on weekends drove around to visit them, happily browsing the whole day.

We drove as far as Maine once. I found so many books on Admiral Dewey who sank the Spanish fleet on Manila Bay in 1899.

You see, Dewey came from Maine, so the citizens of that state were proud of their victorious son and produced not just books, but also medals, tokens, kerchiefs, and many more memorabilia.

Admiral Dewey commemorative plate

There were yearly county fairs, stretching for several acres on fairgrounds, selling everything from used clothes to books all laid out by sellers on portable tables beside their vans.

There were also estate and garage sales. The stuff sold were mostly household stuff and old clothes. But sometimes the house had a library all carted out to the front of the house and books were sold for dimes and quarters. One time, I found a whole album of Philippine revolutionary stamps used on documents.

1970 to 2010 was the height of my book collecting mania. The official historical accounts of the Philippine-American War were plenty and usually written by Europeans and American men who dwelt on the usual subjects: the fighting, the heroic exploits, and the colonial administering. After a while it got repetitious and boring,

I found more interesting the rare accounts of women who came to the country, most of them with husbands who did the colonizing. These women had to keep house and feed and entertain with the help of servants, cooks, houseboys, and the village folk. If they had children, they had yayas.

The women who wrote about their stay in the Philippines made for fascinating reading. Unlike their husbands, they interacted with native Filipinos and had to secure their loyalty and service for the good and safety of their homes. In like manner, Americans and Europeans who came to visit and explore the country, or teach, or just to be part of the islands, wrote with more insightful views of native life.

A historical photo of U.S. officers and women in the Philippines at the turn of the 20th century.

With book collecting came a love for vintage photographs, which usually appeared first as illustrations in vintage books. I eventually purchased photographs and had my first exhibition in 1987 at UC Berkeley along with a catalog and, several years later, another one in a San Francisco Gallery.

In 2011, I published a book entitled A Token of Our Friendship, a study of now-extinct studio photography, with men posing to reveal their friendship.

Which leads me to an important point for fellow collectors to think about. Collecting is a jumping-off point to areas never broached before. The books I bought were initially to be read and enjoyed. But often, I uncovered some facets of our history and culture that were written in passing, but decades, even a hundred years later, were actually important and needed to be explored and shared for the benefit of our society today.

A collection cannot be kept and added to and not opened. Not using a collection is like hoarding and depriving society of a deeper knowledge of our past, of who we are, so that we know where we are going.

A Token of Our Friendship

A collector is also a different breed from an investor. One can be both a collector and an investor. I have no quarrel with an investor who only collects for the purpose of selling at a higher price later. For example, I am downsizing my collection, selling some of the military-war books. Some of these books have appreciated in value because of their contents or just for having been in my library for 30 years. That’s a bonus to me, but it was not in my purpose when I initially bought them. If they should sell well in auction that’s a boon. I am also donating other parts of my collection to libraries.

I’ve continued to make use of my collection, picking out subjects that may interest the public and developing essays and lectures around them. I recently studied the beginnings of the Filipinization of children’s books and found that an African American, not a Filipino, started the process. In 1904, the newly appointed Education Superintendent, Dr. Carter G. Woodson noted that Filipino school children were not interested in American textbooks. He quickly realized that the illustrations in them had nothing to do with Filipino reality. He changed the pictures, from Americana scenes to native ones, from maple trees to bamboo groves. Carabaos still had peculiar nicknames but were better than showing cows.

Dr. Woodson’s revisions worked. Children enjoyed reading their books. There would soon be a demand for budding young illustrators like Fernando Amorsolo. Pepe and Pilar became popular characters and, English literacy increased in just a decade, thanks to Dr. Woodson and his Filipinized books.

Dr. Woodson returned to the United States, applying what he learned, and was responsible for instituting African American History Month. His book The Miseducation of the Negro is a classic and still standard college reading today.

I teach history to public school teachers for an education organization, Synergeia, and found out most teachers couldn’t identify or knew anything about Philip II. Yet, we are named after him. With book research and using the 16th-century Ramusio map, the first to ever name an island Filipinas, I developed an essay and a lecture on the origins of our name. “Filipinas” was first used as a declaration of Spanish ownership, but centuries later used by Filipinos to define ourselves geographically and nationally.

“With book collecting came a love for vintage photographs, which usually appeared first as illustrations in vintage books.”

My book called Loving the Arts examines the basics of art appreciation using Philippine works. Again, my collection of art-related books helped considerably. In effect, I use my collection to expand and enhance subjects not known or are overlooked. And there are limitless topics to examine in Filipiniana today and in the future.

I started to slow down in my collecting. It had something to do with focusing on certain areas, like women’s writing in the Philippines or architecture or languages. They were less written about and hard to come by. The final straw that ended my obsession with collecting Filipiniana is the current job I‘m in.

The Ortigas Library has a collection of over 24,000 books, maps, prints, photographs, and memorabilia, primarily of Filipiniana.

The author’s first exhibit of vintage photographs in 1987.

Attorney Rafael Ortigas amassed the collection from the ‘70s, picking up where Eugenio Lopez, who passed away in that decade, left off. I had met Mr. Ortigas several times before he passed and he was intent on having a public library for his collection, just like Mr. Lopez.

He collected, he said, because he wanted researchers to have access to as much Filipiniana as possible. Most importantly, he wanted the researchers and writers to rewrite or expand conventional historical knowledge. He envisioned a new core of Filipino and non-Filipino historians reclaiming our history with a bias and empathy for Filipinos. In close to ten years as a library we have assisted authors, the media, embassies, and researching students with no visiting charges. The recent bestselling book Rampage by James Scott about the liberation of Manila, was made possible in part by James’ research in our library.

As a collector with a miniscule portion of a collection compared with that of the Ortigas Library, you can very well imagine what came over me. I lost almost complete interest in collecting. What for? Here I was managing a collection beyond my wildest dreams. Every time I enter the closed library section, there is always, guaranteed, a book that I had never ever seen before.

So, what’s the use of collecting? I didn’t want to reinvent the wheel. If I made sure this library ran and served the public, then it would be like sharing a collection. And in the end, collecting for some of us ends up as a matter of sharing. There are others who share their collection, and I want you to know them because they keep our history alive. Aside from the major libraries like the Lopez, the Filipinas Heritage Library, and various university libraries, there are private individuals who share their collection. I must cite Mario Feir, who allows researchers access to his. I want to thank Melvin Lam who has allowed the Ortigas Library to study his collection and share it with the public. He also was responsible for inviting me to be part of the Chinatown Museum series.

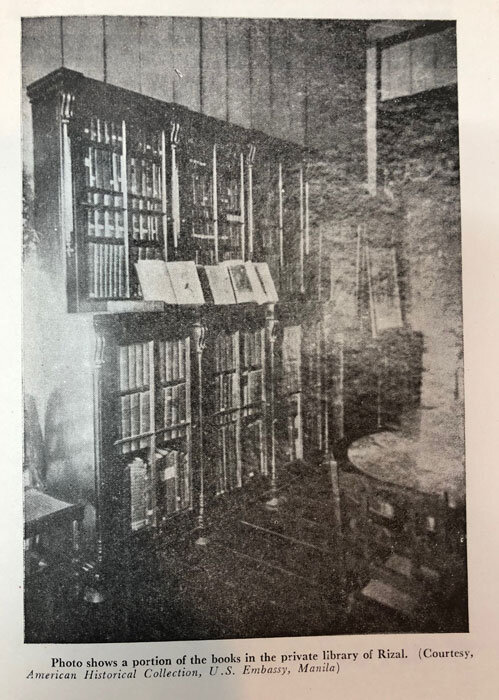

I end with a story of another collector. Jose Rizal collected books. He amassed a collection of 2,000 books. From his collection and his research in the great libraries of Europe, he wrote and published his subversive novels, essays, and short stories, often with borrowed money since his allowance from home wouldn’t arrive on time. Rizal the collector helped lead our country to freedom. But as you and I know, today, we are still bogged by serious problems that need to be addressed.

We will need more collectors than ever before.

This talk was delivered by the author at the Chinatown Museum, Manila on April 10, 2021.

John L. Silva is executive director of the Ortigas Library, a research library in Manila.

More articles from John L. Silva