The Case of the Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation

/Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation by Peter Jamero

Bridge Generation Defined: Children born in America by the end of 1945 to at least one Filipino parent who immigrated to the United States during the early 1900s.

(1) In 1906, a small group of single men from the Philippines were recruited by plantation barons to fill farm labor shortages in Hawaii.

(2) Around the same time, the Philippine government sent groups of students to American universities with the expectation that their education would benefit the Philippines upon their return.

(3) The 1920s-30s witnessed the mass immigration of thousands of single Filipino men to work in Hawaiian plantations; recruiters believed women would not make good workers and discouraged the immigration of a commensurate population of Filipinas.

Today, the Manong Generation is gone but not forgotten, thanks to the documentation of their experiences in America in the classic book America is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan (1943). However, the literature has been silent with respect to the critical need to document their children’s Bridge Generation experiences. Except for memoirs written by Bridge Generation authors during the 1990s -- Vangie Buell’s book Twenty-five Chickens and a Pig for a Bride; Bob Santos’ Hum Bow, Not Hot Dogs; Patricia Justiniani McReynolds in Almost American; and my book Growing Up Brown: Memoirs of a Filipino American – the academic and literature communities have ignored my pleas.

The lack of empirical and evidential documentation of the Bridge Generation’s experiences in America and the fact that their numbers continue to be rapidly declining, are what inspired me to write my second book Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation (2011). Following are summarized excerpts from the book:

General Characteristics

• Since most of Filipino parent(s) of the Bridge Generation immigrated as single men without a commensurate number of Filipinas, their BG children are a racially mixed (mestizo) generation.

• Male children were preferred by their traditional Filipino fathers and provided more freedom.

• Female children were sheltered and raised to learn traditional tasks of cooking, housework, etc.

• All children were primarily raised in the Filipino culture of their fathers.

• The Bridge Generation developed their own identity and sub-culture. Examples -- they used G-language (based on Pig Latin, popular during the 1940s), referred to themselves as Flips, and danced the offbeat to bebop music.

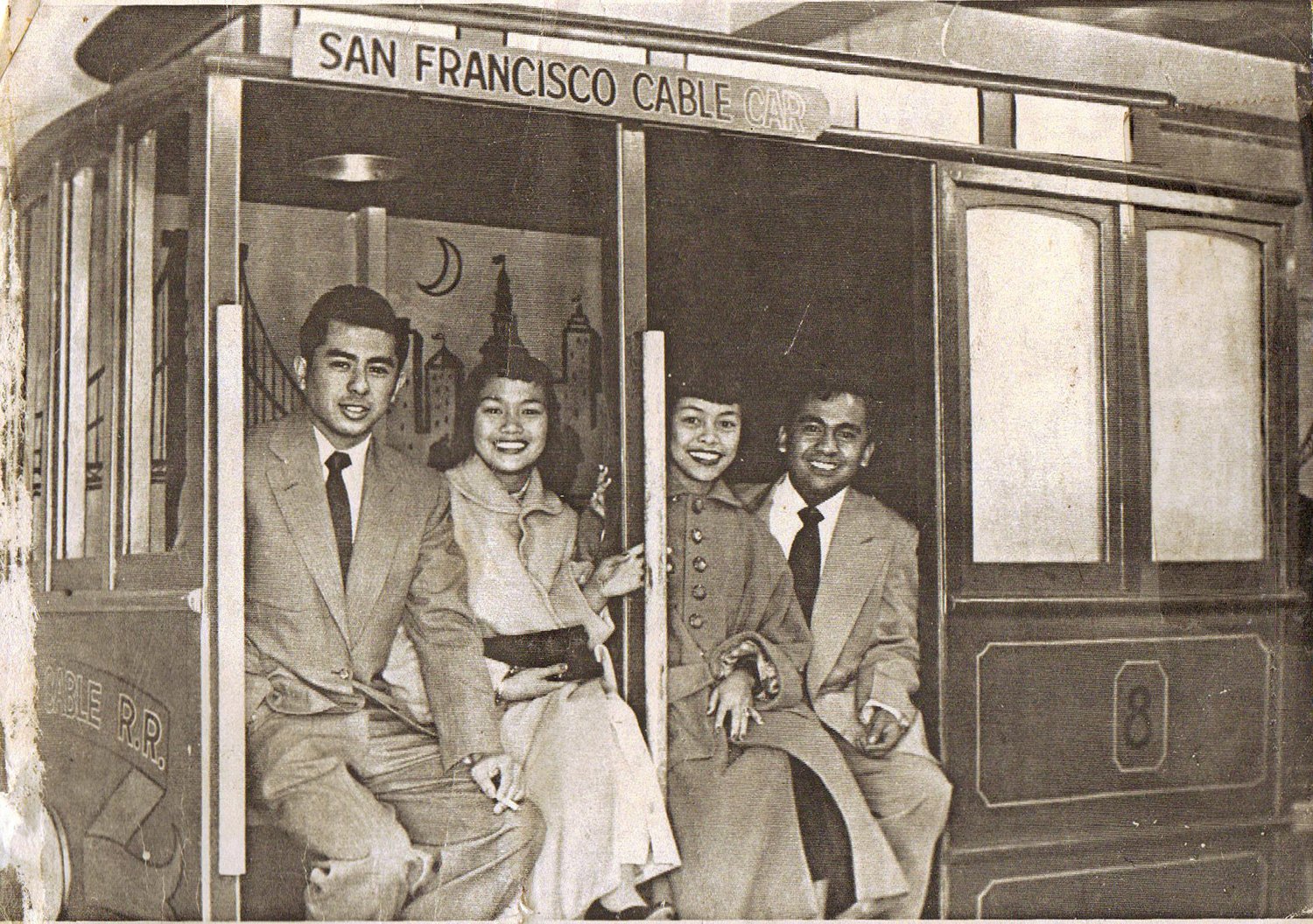

Bridge Generation Youth (Photo courtesy of Peter Jamero)

• They ate steamed rice with their meals.

• They referred to their elders by respectful names, never by their first names.

• They rejected the regional stereotypes of their parents. All were Filipinos – not Ilocano, Visayan, or Tagalog.

• They rejected the colonial mentality of their parents. Whites were not superior.

• They did not share the Filipino passion for sabong (cockfighting).

• They had little or no interest in events in the Philippines.

Growing Up Years – The Great Depression

Anti-Filipino attitudes by white society, fueled by real or imagined threats to Great Depression employment, forced many Filipino families in cities to live in predominantly working class and multiracial enclaves located in the poorest sections in segregated ghettos. For many families, their meals were often rice with soy sauce or mongo beans. Growing up in cities was not easy for young Filipino Americans. In Stockton, downtown businesses routinely posted “No Filipinos Allowed” signs. In San Francisco one was not welcome outside the Filipino business section or their immediate neighborhood.

“Positively No Filipinos Allowed.” at a Stockton hotel (Photo by Sprague Talbott)

Under these circumstances, growing up for the youth meant their recreation and social life was largely spent with Filipino contemporaries. They were welcomed at “flea house” movie houses but rarely at first-run theaters. Boys as young as eight years of age often sold newspapers during weekends. During summer vacations, teenage boys routinely worked in country orchards and farms to help support their families. Youth often endured racial slurs such as being called monkeys.

Growing up in the country was also not easy for young Filipino Americans. Some in the Delta area adjacent to Stockton were required to attend segregated schools. Since child labor laws were rarely enforced and childcare was not affordable, children often worked long hours in hot fields alongside their parents. In Filipino campos, adolescent girls took in laundry from farmworkers. In the lettuce growing Salinas Valley, a 13-year-old boy earned $2 a month as a janitor at his school sweeping floors and cleaning bathrooms.

If you were a Filipino teenager, chances are you dropped out of school to help support the family, particularly if you were the eldest son in a large family. Most likely, you also joined older and more experienced manongs in migratory work in California’s Central Valley and in the fish canneries of Alaska. Like your city counterparts, your social life was largely spent with other Filipinos. And like city Filipinos, you often were subjected to racial slurs. Unlike your city cohorts, however, recreation and social venues were more available to you as you were able to freely cavort in the open fields of the countryside. Moreover, your meals were more nutritious. Pigs and chickens could be raised and slaughtered; vegetables could be easily grown.

Youth from the rural Central Valley enjoy a rare outing in the big city in the 1950s. (Photo courtesy of Peter Jamero)

Bridge Generation youth were strongly encouraged by their Filipino parent(s) to learn English and become educated to better assimilate in America. Most did well in the classroom, were popular, and often were elected as class officers. Outside of school, however, it was not unusual to be socially excluded. After being turned down repeatedly by white girls, a popular Central Valley high school class president came to the realization that the only way he could go to the prom was if his date were of an ethnic minority. Devastated, he chose not to attend rather than be told whom he could bring. In San Francisco another popular high school class president was the only one not invited to a party of class officers. Ironically, the party was held in a Jewish home.

Growing Up Years – World War II/Korean War

Bridge Generation youth came of age during World War II and the Korean War. Young Filipinos did not hesitate to enlist in the armed forces. It was a rare opportunity to demonstrate their strong sense of patriotism and identification as Americans. Many served honorably in the U.S. Army’s First and Second Filipino Regiments, often receiving early promotions as non-commissioned officers. No longer were they called monkeys but “Brave Brown Brothers” -- consistent with the patriotism of the times. After the end of WWII, however, they would again encounter discrimination, particularly in housing. Returning war veterans, now married with children, were routinely denied housing by realtors since housing and civil rights legislation were yet to be enacted.

Korean War veterans also experienced housing discrimination. In 1953, two college students – one of whom received a Silver Star and a Purple Heart for bravery in combat -- were evicted without notice. With no other recourse, identical letters were sent to the college newspaper and the city’s two dailies protesting their discriminatory treatment. The city’s response was virtually non-existent. Most disappointing was the total absence of support or assistance from the established Filipino community.

On a more positive note, Filipino youth clubs sprouted up in every community with a significant Filipino population. It began in 1939 with the establishment of the Filipino Mango Athletic Club of San Francisco, enabling it to participate in city basketball leagues and play nearby Filipino basketball teams on a home-and-home basis. Although World War II would soon interrupt basketball play, the war ironically expanded the youth club movement into an athletic circuit in Northern and Central California. Now in the armed forces, Mango club members met other Bridge Generation Filipinos from other communities and shared their club experiences – not only in basketball, but also as healthy social outlets for Filipino youth to engage in activities otherwise denied them in schools. Competition in softball and volleyball soon evolved; girls organized their own athletic tournaments. Highlighting the tournaments were the awards dances that followed in the evening. For the first time, youth from different communities met and socialized with one another. Moreover, it was not unusual for some to end up marrying out-of-town mates.

The Filipino Mango Athletic Club of San Francisco basketball team. Organized in 1939, the Mangos were the first Filipino American Youth Club and spawned many other clubs in California. Not only did youth clubs provide for inter-community competition in basketball, softball, and volleyball for athletes and their fans; but the tournament dances that followed the games also provided healthy social outlets for all Filipino American young people. (Photo courtesy of Peter Jamero)

Benefits of the Filipino Youth Club Movement

• Youth clubs contributed to developing BG’s own identity by creating a rationale between traditional Filipino culture and American society.

• Tournaments helped youth develop a group identity.

• Social events gave youth a setting where they felt they belonged.

• A support network was created of young Filipinos who shared the same concerns, had common ties to a single ethnicity and faced the same hardships.

• Clubs consisting of peers were a nurturing environment and a haven from prejudice.

• The self-sustaining operation of clubs was a leadership training ground for future success.

Post-war Experiences

The years between the end of World War II and the Korean War were a period of economic growth and stability. Like other American war veterans, Bridge Generation Filipino Americans took advantage of the benefits of the GI Bill and pursued educational and occupational objectives, married and raised families. New products in industry and the beginnings of the service sector provided increased opportunities for work. The traditions of a strong work ethic and high workforce participation learned from their Manong Generation parents were additional incentives for seeking work.

These factors, plus the continuing trend of marrying early, combined to find increased numbers of Filipinos in the labor force. Filipino American high school graduates, who earlier found it impossible to find work, now opted to enter the ranks of the employed. The Bridge Generation greatly benefited from these optimistic years of high employment. Their Manong Generation parent(s), whose hopes of attaining the American Dream had long been shattered by the Great Depression and racial discrimination, could now see hope for their children – if not for them.

My book also discusses two workforce studies conducted by the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS). The first study, conducted in 1998, found the level of educational achievement and workforce participation of the Bridge Generation greatly exceeded that of their parent(s)’ Manong Generation, which had minimal education and was largely relegated to the lowest paying jobs. However, the findings were only from small samples, did not provide comparisons with other groups and were far from definitive.

The second study focusing on individual achievements of the Bridge Generation, conducted in 1994, concluded that the accomplishments of these “Filipino First” achievers, while laudatory, were modest at best. When the studies were conducted in the 1990s, the ranks of the Bridge Generation did not include a CEO of a major corporation, a member of Congress, or artists, engineers, scientists, or attorneys well-known to the American mainstream. Moreover, in comparing the Bridge Generation to other second generation Asian groups, its counterparts have made a much greater impact on America and at a much faster pace.

To conclude, my book clearly identifies the critical need for more definitive documentation and empirical studies of the Bridge Generation. However, as noted in the introduction to this paper, “the academic and literature communities have ignored my pleas.” Sadly, here in the year 2023, that day is yet to come.

Peter Jamero was born in Oakdale, California in 1930 and raised on a Filipino farm worker camp in Livingston , California. Recipient of a master’s of social work degree from UCLA, he is a trailblazer having achieved many “Filipino American Firsts” in his professional career. He is the author of Growing Up Brown: Memoirs of a Filipino American and Vanishing Filipino Americans: The Bridge Generation. Retired, he lives in Atwater, California.

More articles from Peter Jamero