HOCUS: A Leap of Consciousness

/Saul Hofilena Jr., Guy Custodio and Gemma Cruz- Araneta with the artwork “Celestial Chess Players” (Source: Inquirer.net, Photo by Lyn Rillon)

The name “Hocus” is an acronym of the surnames of the two creators of this powerful art HO is Saul Hofileña, the lawyer-historian who dreamed up these images in mythic spirit. CUS is Guy Custodio, a painter and Spanish period art restoration specialist, who was working on an antique church in Bohol when he met Hofileña. Seeing Custodio’s work a delighted Hofileña persuaded him to lend his fine expressionist hand to what was on his mind – a sardonic retelling of the Filipino-Spanish centuries

The Patronato Real that subjugated our ancestors with Cross tightly entwined with flashing imperial Sword is Hocus’s central reality. Giving full play his insights on historical facts, the scholarly Hofileña goes beyond history into metaphysical realm. Angels, saints, and the godhead itself turn into instruments of earthly power in his imagined upside-down world portrayed in Una iglesia antigua de Basey, Samar.

Tracing the indio psyche’s derailment from its organic world makes comparison inevitable between modern, still enslaved indio minds and our uncolonized ancestors long gone. Their spirit is what rose in several uprisings, among them the quasi-religious Basi Revolt in defense of ancestral culture’s ritual intoxication in the 19th century. So enduring is this worldview that it still sustains our severely persecuted katutubo in the 21st century.

Here are some peaks in Hocus’s artful historical teach-in:

Lectores de las palabras perdidas (Readers of the Lost Words) with six blindfolded priests in black, brown and white robes, noses buried in novena, catechism and prayer book “blindly teaching the faith” far removed from the suffering of their conquered flesh-and-blood indios.

Lectores de las palabras perdidas (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Philippines)

The music of the patronato around the famous Las Piñas bamboo organ played by a wigged Spanish governor general surrounded the native principalia, with all other indios and their Muslim kindred standing apart is a strong statement of the abysmal gap between ruler and ruled. A bold indio climbing the organ is trying to reach the top with his crossbow, but another has already hung himself on one side. Meanwhile a richly-robed clergy lounges close to the Crown atop the organ in the grand indifference of the ruling class.

The music of the patronato (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Philippines)

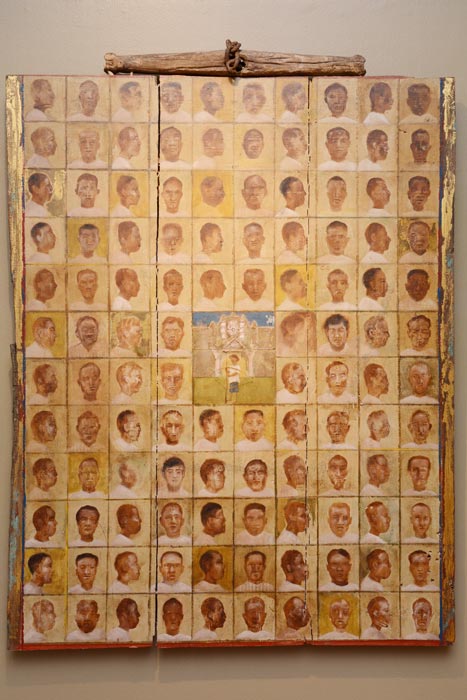

Two close-ups of indios at the peak of friar-dominated rule recreate a reality that still echoes loudly today in Los filipinos, a tableau of obscure indios trapped in “the Empire of the Friars.” Hofileña reflects with fellow historian Milagros Guerrero that they were the very “reason the friars willed Rizal’s death”, fearing mass awakening “from centuries of slumber caused by religion.”

Los Filipinos (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Philippines)

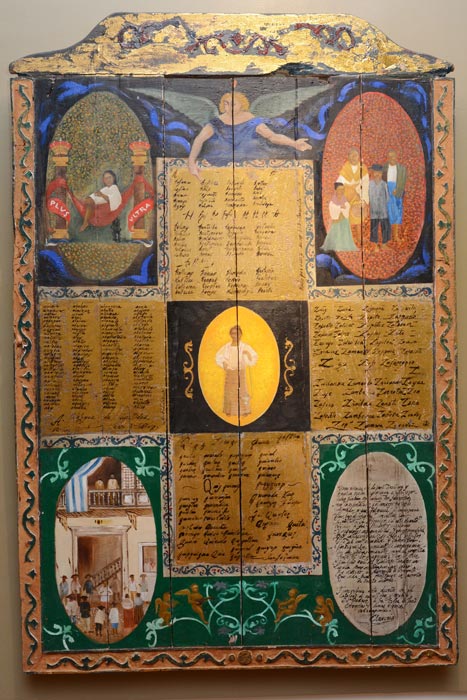

How we lost our names next tells the tale of Governor General Narciso Claveria’s decree for all indios to change their surnames from a Catalogo Alfabetico de los Apellidos. Claveria’s purpose was to ease tax collection and other administrative concerns.

How we lost our names (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Philippines)

But Hofileña points out contemptuous malice in the inclusion of Spanish names for “human ordure (cagas) vices, ailments and deformities.” Indios forbidden to learn Spanish had no way of knowing what their adopted names meant. These humiliating surnames retained to this day were moreover enforced with a draconian hand.

Hofileña notes: “Local government officials and parish priests were instructed not to issue permits or official documents to natives whose surnames did not appear in the Catalogo. Those who reverted to their original surnames after registering their new ones were penalized with a jail term.”

The rout of the indio mind was almost complete by then. Nearly all of Luzon and the Visayas complied, except for “pockets of resistance in Laguna and Pampanga” and the Cordillera peoples who resisted the friars from the start.

Now we arrive in Puente de capricho, The Bridge of Caprice, an unfinished bridge in the Franciscan settlement of Majayjay, Laguna. Here Dominicans are climbing a wooden ladder to a showdown with their rival Franciscans atop the bridge, both wielding religious icons as weapons of war. Meanwhile Rizal, Noli and Fili underarm, escapes in a boat as a babaylan sends warning signals from the riverbank. Rizal’s words come alive in a mother dog attacking a crocodile for killing her pup on the opposite shore. Mother Filipinas is reaching boiling point, but under the ladder an india water carrier is torn between the friars and Rizal – just like today’s Filipinos caught between freedom and compromise with new tyrants.

Puente de capricho (Photo courtesy of the National Museum of the Philippines)

This footnote on religious orders competing for territory resonates in today’s shortage of agricultural land disturbingly converted into vast industrial plantations and urban real estate by a mostly Catholic-schooled Filipino elite defying land reform.

Next Celestial Chess Players has two cowled monks playing chess – Spaniards as white pieces, indios as black. Their game is mirrored in a heavenly chessboard held aloft by two angels, one cheering for justice, the other for truth. But frailes subverting the spirit of Christianity’s founder play a fixed game. White is routing black, but already an absent white king leaves black nothing to win.

Finally, La pesadilla, The Nightmare, a grand triptych Hieronymous Bosch would have applauded. After nearly a year of unbridled extra-judicial killing in our country, the eye is caught first by Christ’s Crucifixion at center and a surreal feast of killing replete with skeletons below. Around this mass murder are soldiers all in a row with resisters of ongoing slaughter facing a brooding mass of defiant humanity on the opposite side. Light and dark winged beings fly over the whole horrific scene.

La pesadilla(Source: Inquirer.net, Photo by Lyn Rillon)

These are “nightmares in my mind,” Hofileña confesses. “I see death in various forms – mga araw na walang Diyos post-Golgotha and pre-Resurrection. Good and Evil are in a fierce and perpetual battle for hegemony over the Earth and its creatures.”

This intense drama of life and death, freedom and slavery curated by Gemma Cruz-Araneta opened on Easter week. The National Museum judged it significant enough for six months on show. You have till October to contemplate its phantasmagoric images of colonized indio soul still struggling to break free in the 21st century.

Sylvia L. Mayuga is a veteran Filipino writer on the arts, culture and history of the Philippines. She has three National Book Awards to her name.